At that time, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, did not allow African American artists to enter the competition. Jones needed her white friend Céline Tabary to deliver the painting.

Eventually, Jones would win the acclaim she deserved, both in the U.S. and abroad. To understand how Lois Mailou Jones achieved recognition on her own terms, travel back in time with us—to Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts; to Paris; and to DC.

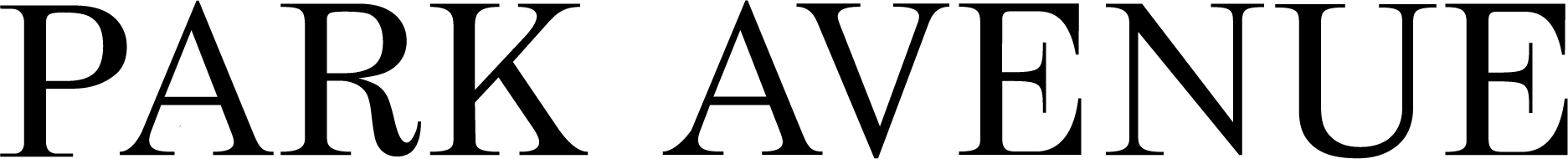

Lois Mailou Jones, Indian Shops, Gay Head, Massachusetts, 1940, oil on canvas, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the artist), 2015.19.212

Consider, for a moment, the sunlit scene within the painting. On the horizon, the sun’s rays glitter across the water. Close your eyes, and you might feel the warmth of the summer breeze on your skin and the sand gathering between your toes. The salty sea air and summer heat radiate from this seaside scene. And at the heart of the painting is a uniquely mid-20th century, middle class African American experience.

Jones painted this landscape in what was then the town of Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard Island. Just across the island on its northern tip was the site of her childhood summer vacations: Oak Bluffs. The Black enclave offered a rare place of rest and safety for a Black woman before the civil rights era in the United States.

Ouida F. Taylor, Photograph of Taylor family members at the beach on Martha’s Vineyard 1950s. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Dr. Teletia R. Taylor and descendants of Geraldine A. Taylor.

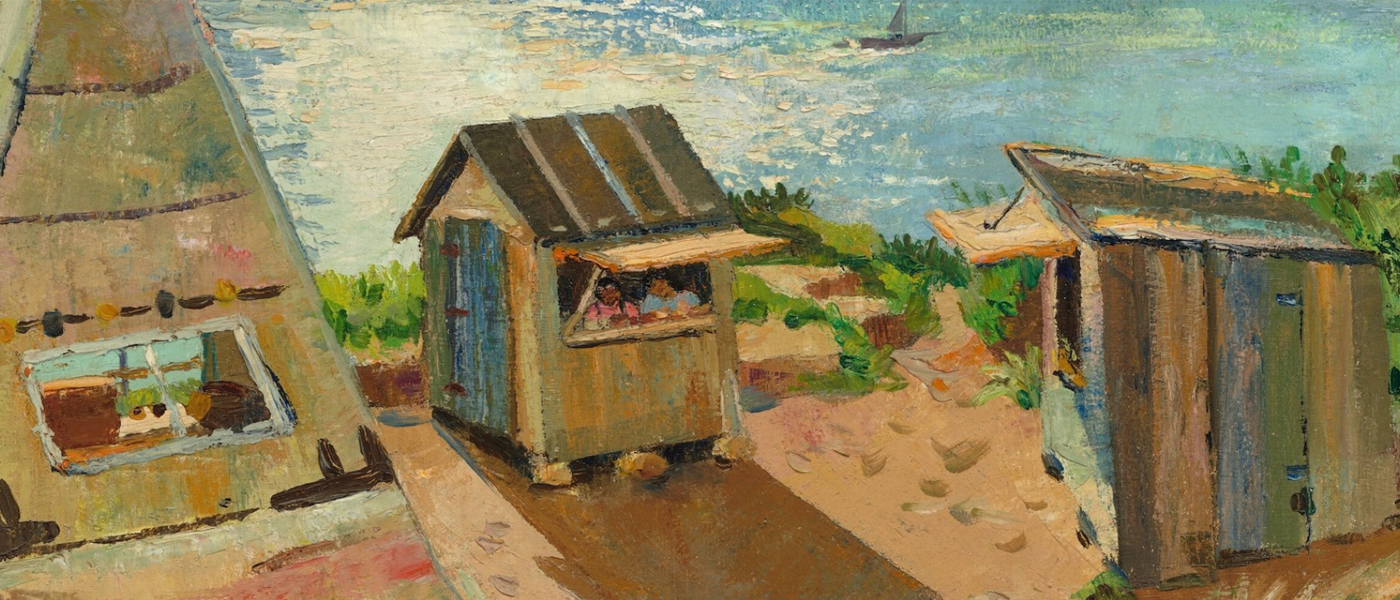

At a time when white segregationist policies excluded African Americans from most beaches and pools, Oak Bluffs was one of the few places in the country that was safe for Black leisure. Middle- and upper-class Black vacationers bought summer homes and made annual trips to the island. Oak Bluffs gave them a reprieve from the everyday racism they faced on the mainland, a chance to gather and be among community.

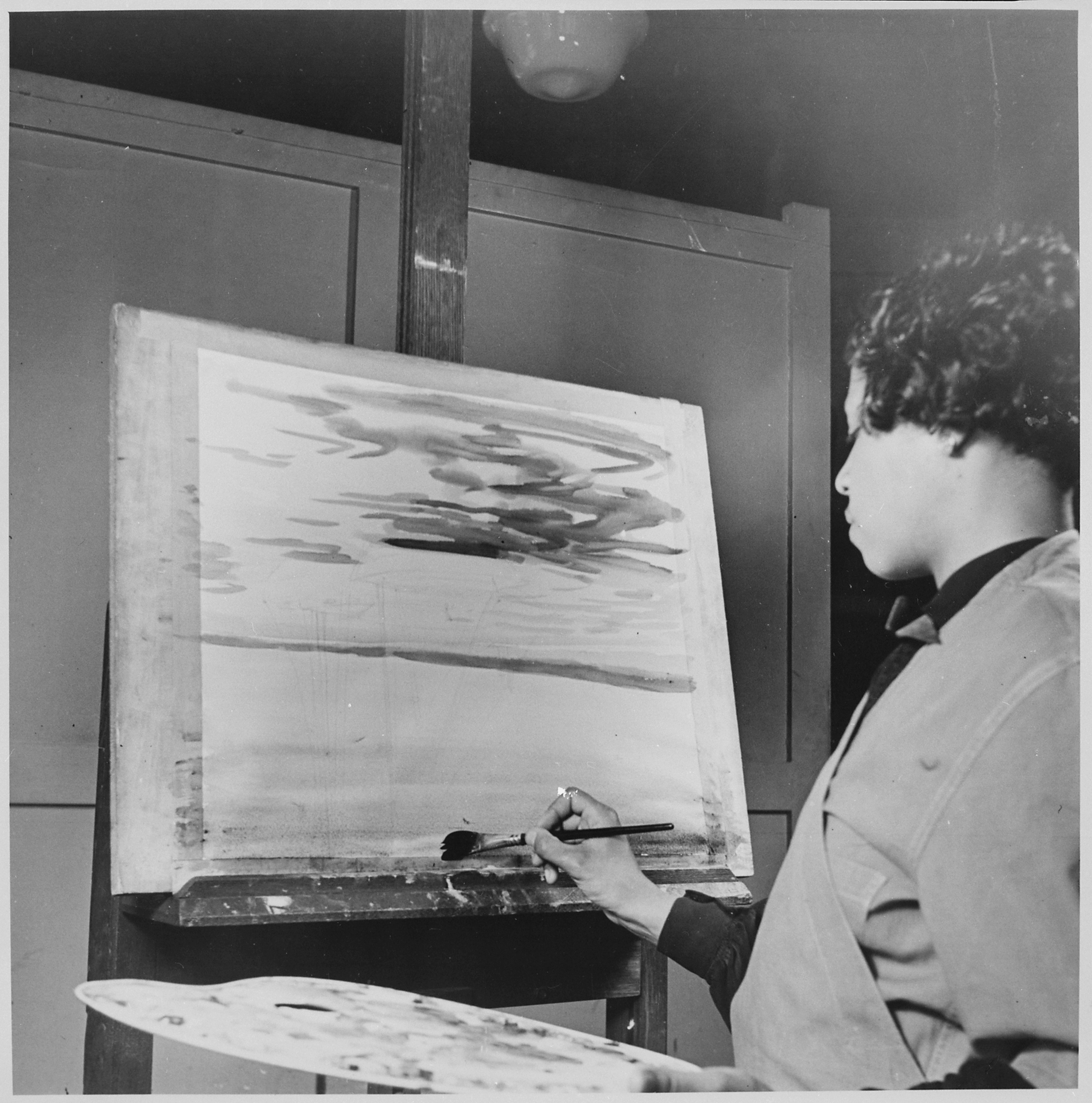

Jones’s maternal grandmother began summering at Oak Bluffs in the late 1800s, and Jones grew up coming to Martha’s Vineyard every summer. It was the beauty of the island—its blue waters and white sands—that first inspired her to paint. Her mother even “exhibited” Jones’s early watercolors of the island on the family’s clothesline.

Unknown photographer, Lois Jones, artist and teacher, 1936/1937, negative, National Archives and Records Administration, The Harmon Foundation Collection.

Unknown photographer, Lois Jones, artist at work, 1936/1937, negative, National Archives and Records Administration, The Harmon Foundation Collection.

Her summers at Oak Bluffs set Jones on a path to Paris. Two friends she met on her vacations, artist Meta Warrick Fuller and composer Harry Burleigh, told her that to be successful, she would have to go abroad. They pointed to artist Henry Ossawa Tanner, who went to France to paint because of the discrimination he faced in the US. As Jones put it, “This country wasn’t interested in exhibiting our work or allowing us any of the opportunities that the white artists enjoyed.”

In 1937 Jones followed her friends’ advice. She took a sabbatical from teaching at Howard University in Washington, DC, to study at the Académie Julian in Paris. In an interview with the journal Callaloo, she recalled, “France gave me my stability, and it gave me the assurance that I was talented and that I should have a successful career.”

But Jones, like many travelers to France, discovered that her French wasn’t good enough to keep up. The directors of the school appointed fellow student Céline Tabary to interpret for her. The two became fast friends. Jones’s mother invited Tabary to visit them in the US in 1938. After World War II broke out, Tabary couldn’t return to France and remained in Washington, DC, until the 1950s.

Artists of the “Little Paris Group,” 1948. Céline Tabary is on the staircase on the left, Loïs Mailou Jones is seated on the right facing away from the camera. Alma Thomas papers, circa 1894-2001. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

While in the US, Tabary, a white woman, would take Jones’s paintings to competitions. The juries never knew that the artist was Black. In Jones’s words, “that was very much in my favor.”

Jones would often visit the institutions that hung her works and stand in front of her paintings. She recalled:

“The guard saw me looking at the painting and said, ‘I guess you like art, don't you?’ I said to myself that he doesn't know that the painting is mine hanging there. And so that's how it was way back in those early days; I was exhibiting at all of the big museums, but they never knew that I was black because I either shipped my works or had a white person deliver them. Now you see how difficult it was.”

When Jones won the prize for Indian Shops, she accepted the award by mail to keep her race hidden. Fifty years later, the Corcoran Gallery hosted a retrospective show of her works and publicly apologized for their discrimination.